I am the Assistant Director, Photographer, Artist and Designer for the South Asasif Conservation Project, an archaeological dig in Egypt.

I designed the Project’s official website, where you can learn more about the work we’re doing in Egypt, reconstructing a necropolis of ancient tombs.

The latest updates about current work seasons are posted on the Project’s blog. We are now open for our 2021 Season.

I try to make myself useful around the site, spending most of my time in Egypt crawling into deep, dark holes, climbing vertiginous ladders, or scrambling onto various rickety articles of furniture to find just the right angle for a photograph, help place an ancient fragment in its original location, or participate in a new discovery.

Exhibitions

I designed two exhibitions of our best finds for the Luxor Museum.

South Asasif Necropolis: Journey Through Time (2019)

You can read my essay from the catalogue about how the exhibition design was inspired by German Expressionist silent film here:

The South Asasif Pyramidion (2020)

Articles on archaeology for the Australian children’s history magazine, HistoriCool:

“Animals of Ancient Egypt.” HistoriCool Magazine, no. 16, Sept. 2015.

Birth of an Archaeovoyeur

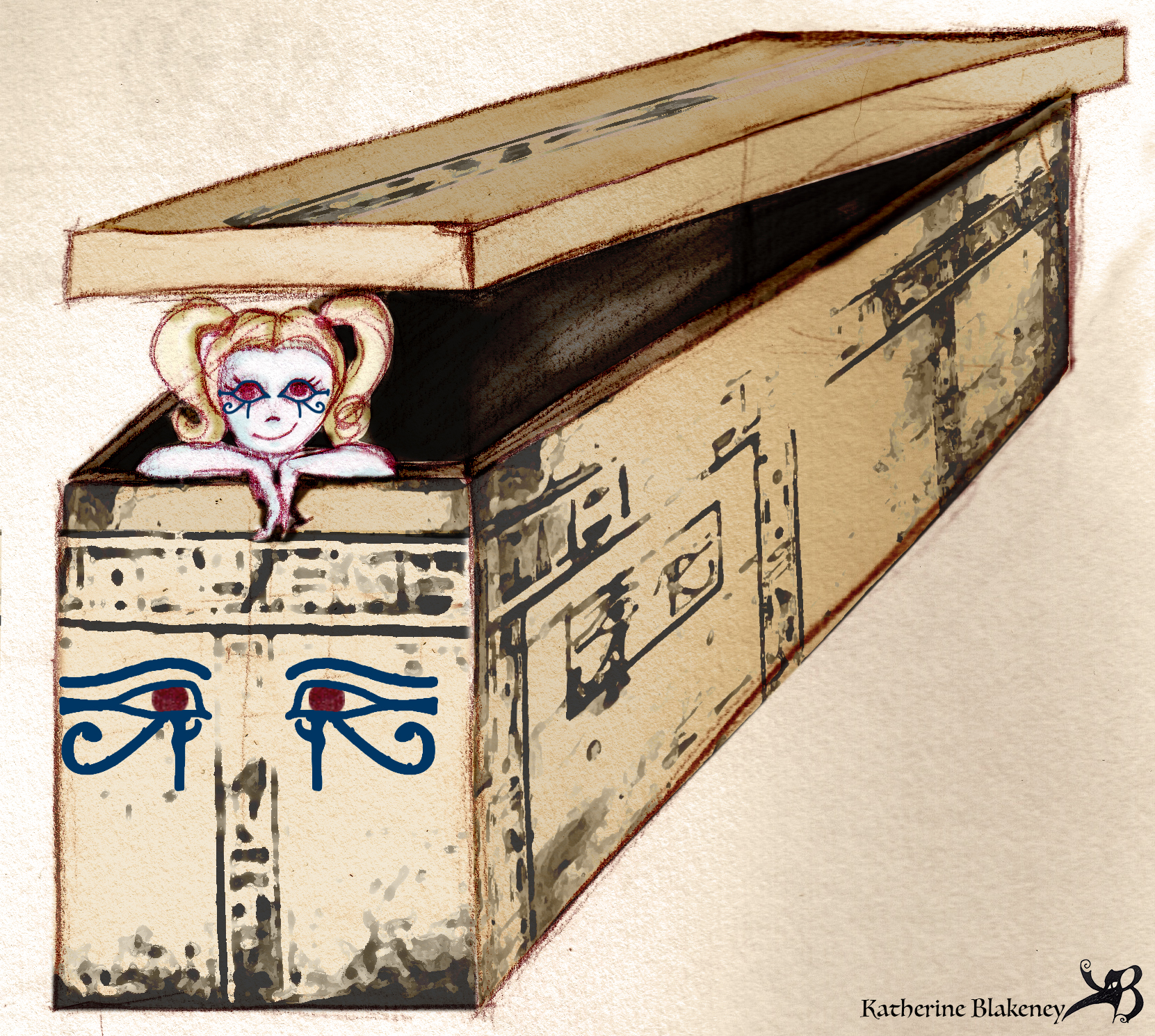

I was born in a coffin.

Or so some people believe. People who know me and can find no other explanation for why I am the way I am. I can’t be a hundred percent certain this claim is untrue. I’m sure the coffin was a very cozy one, made of fragrant wood with hieroglyphic inscriptions traced in Egyptian blue.

It wouldn’t surprise me, having spent most of my childhood between museums and excavation sites. They were my home, my sources of education, entertainment, horror and delight. I helped record mummy bones when I was nine and struggled through my French homework in the open court of an ancient Egyptian tomb when I was thirteen. Every day after school, I’d walk to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, to relax in the company of the ancient monsters that filled its galleries. Assyrian lumasi, Japanese demons, many-armed Hindu gods and mythic creatures of every variety.

In their company I gained some useful life skills, found my closest friends, my first pets, my mentors and my love interests. I suspect I may have become one of them in the process.

There’s no other way to say it – I’m a dig brat. Though I’ve gained professional degrees in both the making and history of art, I can’t bring myself to see art and archaeology as professions or hobbies. They’re a way of life. They’ve fused inexorably with my DNA and it’s too late to seek a cure now.

The good news is, my terrible affliction has given me superpowers! It’s made me archaeovoyant.

Allow me to explain.

Some unfortunates see dead people. Some foresee the horrors of the future. Others can move objects with their mind. I see archaeology. Everywhere. My mental tentacles absorb it from every aspect of life, nature and popular culture. Whether the archaeological element is intentional or non-diegetic, little red lights ignite behind my eyes and a beeping sounds deep in my inner ear until I discover the cause.

And that’s why I started this blog.

I won’t be teaching you how to diagram the location of a find on a top plan or how to discover a lost tomb crammed with golden statues. An archaeological textbook will help you with the former and a harsh reality check with the latter.

I won’t be judging the veracity of cultural representations of archaeology. Here’s a revelation – they’re all wrong. I’ve been working on a real dig since I was nine. Yes, being an archaeologist is tough. Yes, it takes an obscene amount of education. Yes, it involves long hours of completing meticulous and unromantic tasks such as counting thousands of beads by hand. I’m also a filmmaker and film historian and appreciate that no one wants to see this in a thrilling adventure film. Neither do I, because on the best days archaeology can be every bit as exciting, romantic and breathtaking as you imagine. There’s nothing wrong with admitting that.

I also won’t be restricting myself to topics that fall under terms such as “Egyptomania” or “Archaeomania.” They don’t even begin to cover my twisted relationship with archaeology.

In short, this blog isn’t about archaeology. It’s about Gothic novels and children’s picture books, about popular TV shows and eighteenth-century poetry, about action films, animation, cartoons and science fiction stories, computer science, cookbooks, board games, fashion, costume jewelry and pencil cases shaped like sarcophagi. It’s about every seemingly random thing that tickles my archaeo-senses and that I hope will appeal to my fellow archaeovoyeurs.

I invite you to venture into my treasure trove and view the results of my scavenging. In time, I hope you’ll share some of your treasures in return.

Mummy Fakers in Silent Film

The holiday season is a time to reflect on our values and appreciate the things that make us happy – family, friendship, good food, cozy homes, and of course . . . mummies.

I confess I did my utmost to frighten you with my horde of Silent Era mummies this Halloween, but they all let me down. One romantic maiden after another, wearing their bandages like sheer evening gowns. I’ve decided to change my strategy and rally my silent mummies for another assault. If we can’t make you scream, perhaps we can make you laugh.

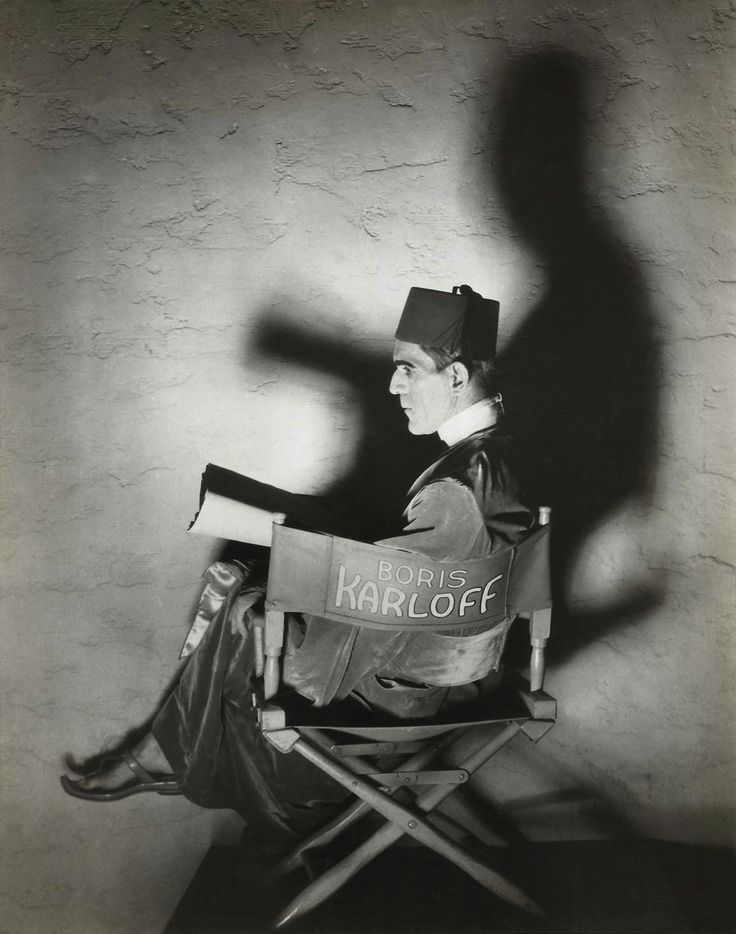

As I pointed out in my earlier post, Mummy Love: Cleopatra as Cinema’s First Mummy, the mummies of silent film were not the vindictive monsters we know today. I like to refer to this period as BBK (Before Boris Karloff).

In the over twenty mummy films made in the first two decades of the twentieth century, you’d be hard pressed to find a single homicidal maniac or even a meagre flesh-eating scarab. Before Karloff’s undeniably memorable appearance in 1932’s The Mummy, bandaged ancient Egyptians were commonly envisioned either as objects of exotic passion or broad comedy (frequently a bit of both). These seemingly contrasting approaches mirrored the dualistic nature of early twentieth century archaeology and its impact. The oft-retold tale of the feminine mummy rescued by a dashing Egyptologist romanticized the process of exploration and glamorized archaeology. Its dark comedic counterpart ridiculed the pretensions of self-proclaimed scholars and the surrealism of commodifying preserved human remains.

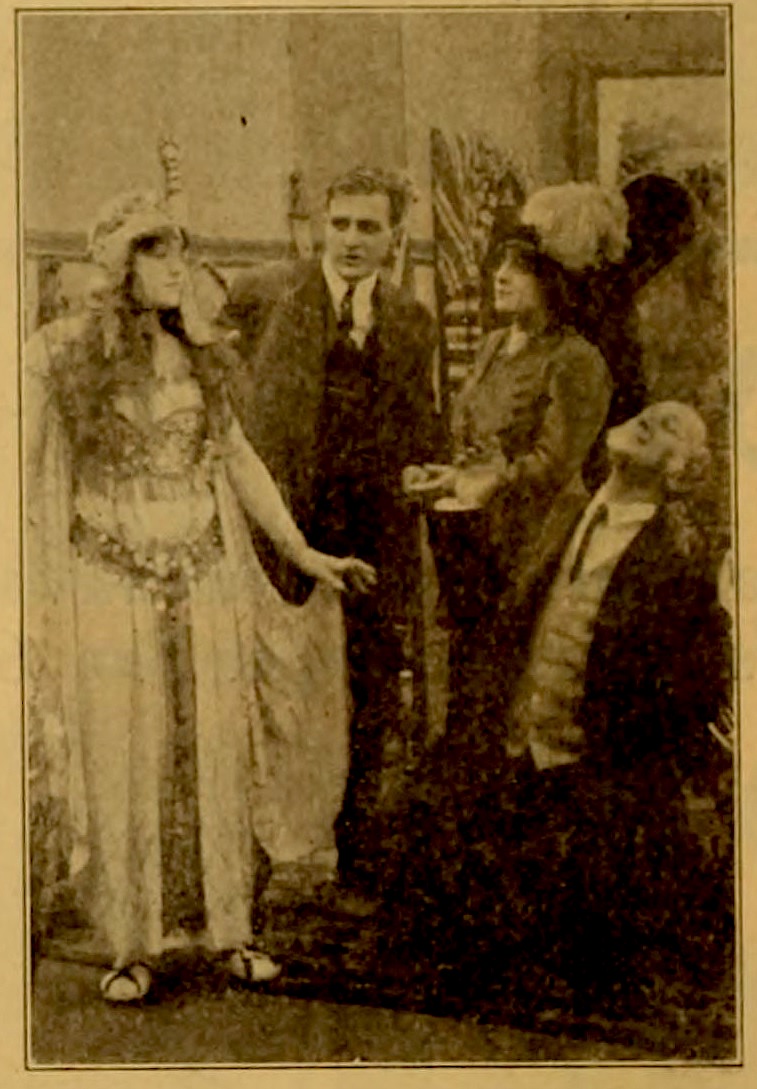

The very real criminal practice of selling falsified mummies and mummy bones to eager scientists and gullible tourists inspired an entire sub-genre of macabre comedy. This type of mummy story was the domain of pranksters, mountebanks, tramps and hapless professors and took a distinctly theatrical and flamboyant approach to its subject. A number of these films center around professional mummy impersonators – live people posing as mummies to defraud scientists out of large sums of money. This alarming topic is explored in depth in the 1915 British short The Live Mummy. In 1912’s The Mummy and the Cowpuncher, an actor goes so far as to impersonate a professor, displaying his daughter as a miraculously preserved princess at his lectures. A similar underhanded scheme appears in other films such as Eyes of the Mummy Ma (Germany, 1918). Such men give a bad name to mummy-fakers and ought to be ashamed of themselves.

But not every false-mummy scheme was purely nefarious in intent. Silent filmmakers would have us believe such means could be used to achieve a nobler end. Namely, a happy marriage. Allow me to elucidate.

Thanhouser Films’ The Mummy (1911) and two American films, both made in 1914 (one by Vitagraph, the other by Kalem) – both imaginatively entitled The Egyptian Mummy – all present a common dilemma. Each of these films features a professor father who is either too wrapped up in his scholarly musings or too haughty to appreciate the charming but gormless Jack or Dick who’s stolen his beautiful daughter’s heart. * Note to the wise – if you must get a PhD in archaeology, avoid spawning a beautiful daughter at all costs. * In all three cases, the young men attempt to ingratiate themselves with the professorial father with a peace offering in the form of a mummy. The results of this gesture vary.

In Thanhouser’s The Mummy, the romantic youth (Jack in this case), makes the unfortunate mistake of electrocuting his mummy. The ravishing ancient princess, who hasn’t aged a day in the last 5,000 or so years, instantly forms an ardent attachment to him, almost losing him the love of his modern sweetheart before turning her amorous eye on the professor instead. What’s a several-thousand-year age difference when it comes to true love?

The two Egyptian Mummy films take a more cynical angle involving brainwashing and swindling. Young Dick (from the Kalem film) takes it upon himself to impersonate the mummy of Ramses III (the reason for this choice is clear only to Dick). Narrowly avoiding a live dissection, Dick rushes to give the professor marital advice in sepulchral tones. If this sounds like a far-fetched plan to you, you should see its success rate. That year’s second mummy-peddling suitor (also Dick – evidently a common name for morally dubious young men) takes it a step further, making a tidy profit into the bargain. When his sweetheart’s father offers a large reward for a genuine mummy (in the local paper, no less), Dick takes the wise precaution of hiring someone else to play the role of the mummy before selling it to the professor. The fact that the “mummy” is really an alcoholic bum who’s very much alive shows that Dick isn’t one for planning ahead.

I would tell you how it turns out, but as this film has miraculously survived the ravages of time and space-saving studio bonfires, I’m sure you’d rather find out for yourself. I’ve included a link at the end of this post.

On a more sombre note, the French film Romance of the Mummy (1911), warns of the dangers of violent emotional attachment to mummified seductresses. A young English lord nearly “loses his reason” over the mummy of an (inevitably) beautiful princess that he brings back to his estate. Her image haunts his dreams until salvation comes in the form of a modern girl who just happens to be the princess’s reincarnation. May we all be fortunate enough to meet a soulmate who’s a dead ringer for our favorite ancient corpse. I’m still looking for my own Seti I.

It seems to me the lesson imparted by these films is clear. Impersonating a mummy is a dangerous and complicated business, but so is finding a soulmate. May you spend your holidays surrounded by those you love, whether they belong to our time or have touched your heart from across centuries.

Here are links to more information on the films discussed in this post:

Preserved

• The Egyptian Mummy (Vitagraph, 1914)

Lost Films:

• The Mummy (Thanhauser Films, 1911)

• Romance of the Mummy (Pathé Frères, 1911)

• The Egyptian Mummy (Kalem, 1914)

Mummy Love: Cleopatra as Cinema’s First Mummy

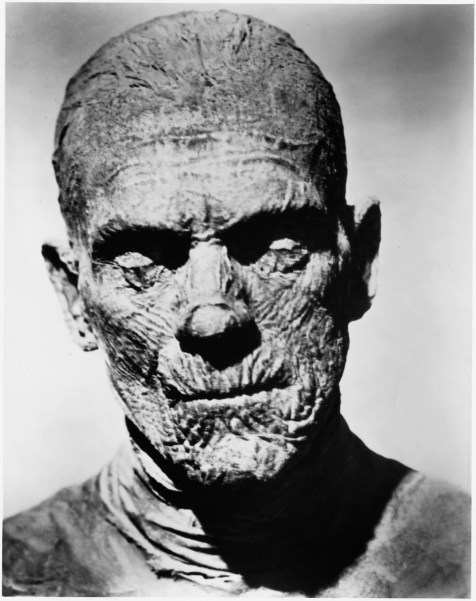

Halloween is my favorite day of the year and I spend most of October preparing to celebrate this glorious day of darkness, monstrousness and decay. Hoping to scare my friends into the holiday mood I planned to make this post as bloodcurdling as I possibly could. And what better way to scare an archaeology lover than with a thoroughly terrifying mummy?

So far so good. Now, to choose the right one. The phantom of Boris Karloff comes to mind at once, but I suspect he is all too familiar to you already. To scare you properly I resolved to delve into uncharted waters, into my favorite era in cinema history – silent film. Considering that the earliest known film featuring the character of an Ancient Egyptian mummy was made in 1899, I had a lot of resin-stained bandages to wade through in search of my silent horror monster.

To my great regret, all I brought back from my journey into the afterlife was a flock of mummified damsels in distress. I apologize, but it is my lamentable obligation to present you with a parade of fair Victorian maidens clad in fashionably draped bandages. I can only assume that with all the glamorous dinners in Egyptian tombs and mummy unwrapping parties held at the turn of the 20th century, mummy bandages were seen as rather alluring.

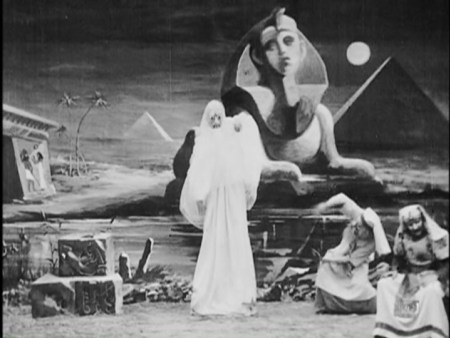

That first cinematic mummy of 1899 graced a humorous trick film called Cleopatra’s Tomb, directed by French illusionist and special effects pioneer Georges Méliès. It centers around a seductive female mummy reanimated by a prying archeologist who loses no time in falling for the “monster” he has unleashed. Perhaps a horror story in the making, but there’s no sign the film had a sequel. From this early cinematic experiment until the mid-1920s, around twenty films were made with titles containing the keyword “mummy.” I’m rather partial to Romance of the Mummy, Mummy Love and The Eyes of the Mummy. The Live Mummy and The Missing Mummy aren’t bad either. The above number includes the United States, United Kingdom and France alone, roughly translating to 2-3 mummy-themed films a year (all referring to a preserved ancient body rather than a maternal parent). Many of these films are unfortunately lost and we have no way of knowing how many more were burned in studio backlots to make way for newer and more fashionable films. Incidentally, burnt celluloid was once widely used by conservators of Egyptian art as a solidifying protective varnish. I suppose we know what really happened to all those unwanted mummy movies. How’s that for a horror story?

But what about lumbering revenants slinking out of sarcophagi in the night, muttering ancient curses under their breaths as their embalmed fingers crush the tracheas of solid modern citizens? Ask Boris Karloff.

The familiar image of the vindictive monster-mummy as seen in the popular The Mummy franchise (1999-2008), didn’t come into its own until Karloff’s Imhotep in the 1932 horror classic The Mummy. Most of the mummies of the Silent Era, as seen in films such as 1911’s The Mummy or the 1918 German film Die Augen der Mumie Ma (Eyes of the Mummy Ma), are not vengeful killers, but rather exotic ingénues in search of rescue at the hands of a strong and silent archaeologist. These films have little or no connection to the horror genre as we know it today, traversing the spectrum from comedy to romance. A lighthearted approach to a macabre subject and a reflection of contemporaneous perceptions of archaeological finds and archaeologists themselves.

Even an ominously titled film like 1903’s The Monster (another Méliès short), is really a farcical love story about an Egyptian prince who resorts to dark magic to resurrect his mummified lover. (I encourage you to consider the results by clicking the link included at the end of this post before you attempt this at home.)

Overall, the resurrected mummy of the early 1900s and 1910s brings to mind Théophile Gautier’s 1840 short story, “The Mummy’s Foot” rather than the costume rack at your local pharmacy. Gautier’s mummy, who comes to collect her stolen foot from a Parisian antiques collector, is not a psychopathic priest but a beautiful princess. She uses charm and bargaining skills rather than violence to achieve her aim, bartering her mummified foot for a statuette. The story is humorous, but it also presents the mummy as mysterious, desirable and ultimately benevolent. Thanhouser Company Films’ The Mummy (1911) also centers around a mummified Egyptian princess stranded in the midst of modern society. Revived by an electric current, she instantly forms romantic designs on a young Egyptologist – greatly vexing his fiancee. There are no ancient curses here, and the story ends not with a battle but with a wedding as the amorous princess finds a widowed professor to marry – a fortunate solution for all involved.

Eyes of the Mummy Ma (Lubitsch, 1918) injects additional drama into the ubiquitous tale of the undead singleton. This entry features a villainous Egyptian hypnotist (Emil Jannings) forcing a living maiden (Pola Negri) to impersonate the eponymous mummy. In a not-so-shocking twist she is rescued by a heroic European painter who brings her home with him to be his muse. The film celebrates her exotic allure while at the same time hinting that she’s far better off in the care of civilized Europeans. It’s all very well being a rescued mummy, as long as you don’t get your bandages caught in the teapot while entertaining guests.

This post hasn’t gone at all the way I envisioned. Instead of making you scream and run, my ferocious cinematic mummies pine for your love and attention, painting lovely watercolors as they wait for the right archaeologist to come along. Perhaps this is a terrifying prospect after all?

If you’d like to adopt a mummy this holiday season you can take your pick by exploring the links I’ve collected below, leading to preserved and restored silent films where possible or to stills from those that became conservation materials.

Preserved:

The Monster (Georges Méliès, 1903)

The Eyes of the Mummy Ma (Die Augen der Mumie Ma, Ernst Lubitsch, 1918)

Lost Films:

Cleopatra’s Tomb (Georges Méliès, 1899)

The Mummy (Thanhauser Films, 1911)

“The Mummy’s Foot” (1840) by Théophile Gautier